The initial evaluation should be focused on screening for specific risk factors that would alter the appropriate treatment . The predictors that have been identified as being associated with an increased risk of complications during follow-up are tamponade, recurrences and constriction. Other predictors, called minor risk factors, should also be considered. These are based on expert opinion and literature review, including acute pericarditis associated with immunodeficiency, trauma, anticoagulant therapy and myocarditis . Any clinical presentation that may suggest an underlying aetiology (e.g. a systemic inflammatory disease) or with at least one predictor of poor prognosis warrants hospital admission and an aetiology search. Patients without signs and symptoms of systemic inflammatory disease can be managed as outpatients with empiric anti-inflammatories and short-term follow-up after one week to assess the response to treatment.

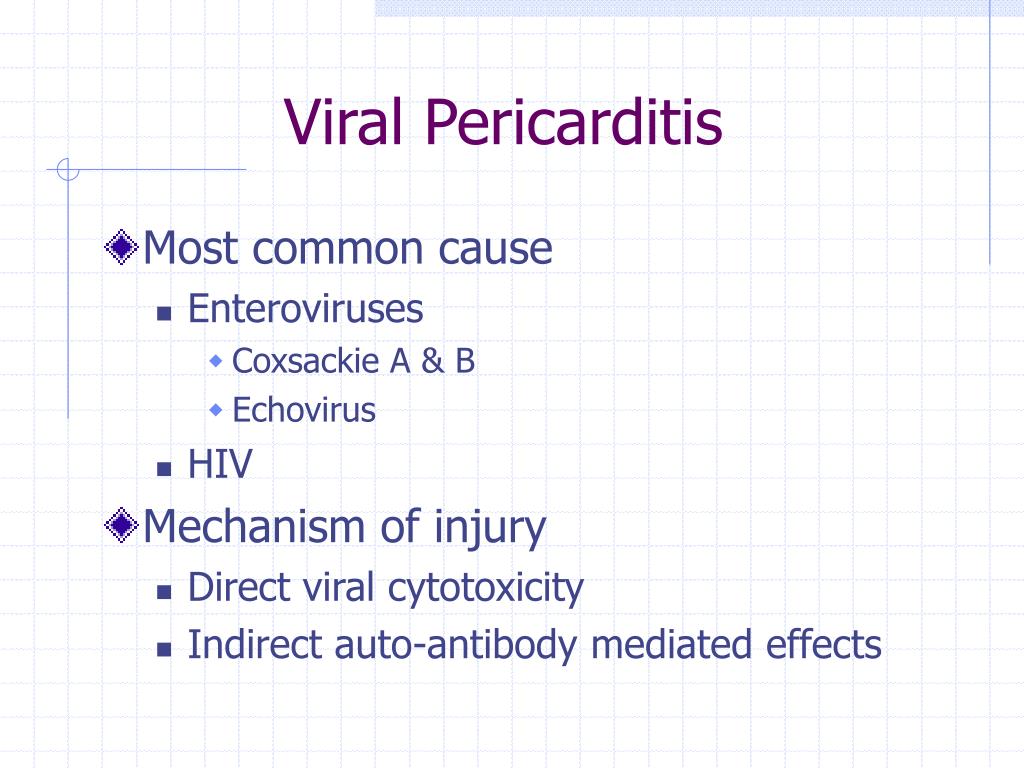

In patients identified with a cause other than viral infection, specific therapy appropriate to the underlying disorder is indicated, and the epidemiological background (high vs. low prevalence of TB) should be considered . Myocarditis and pericarditis are inflammatory conditions of the heart commonly caused by viral and autoimmune etiologies, although many cases are idiopathic. Emergency clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for these conditions, given the rarity and often nonspecific presentation in the pediatric population. Children with myocarditis may present with a variety of symptoms, ranging from mild flu-like symptoms to overt heart failure and shock, whereas children with pericarditis typically present with chest pain and fever. The cornerstone of therapy for myocarditis includes aggressive supportive management of heart failure, as well as administration of inotropes and antidysrhythmic medications, as indicated.

The acute management of pericarditis includes recognition of tamponade and, if identified, the performance of pericardiocentesis. Medical therapies may include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine, with steroids reserved for specific populations. This review focuses on the evaluation and treatment of children with myocarditis and/or pericarditis, with an emphasis on currently available medical evidence. Symptoms can include shortness of breath, chest pain, decreased ability to exercise, and an irregular heartbeat.

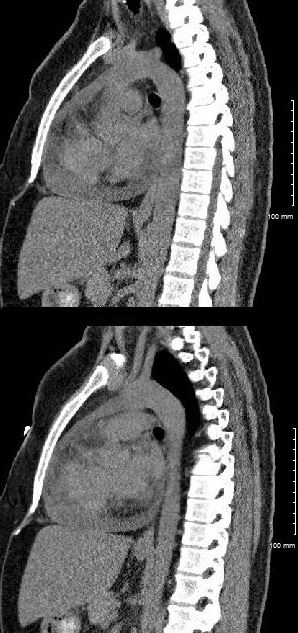

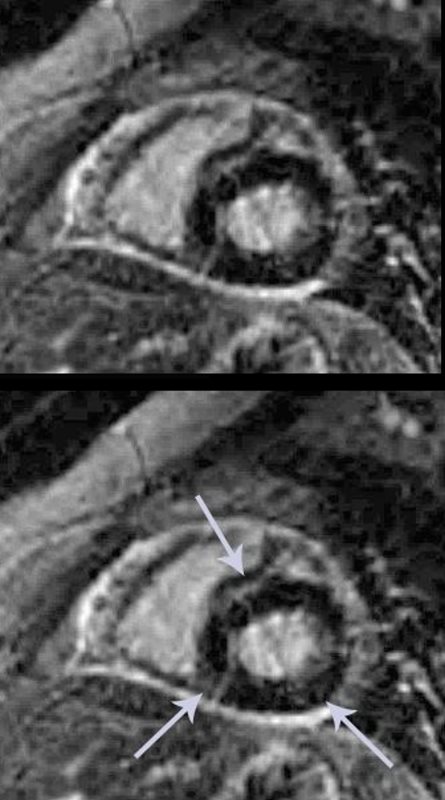

Complications may include heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy or cardiac arrest. In mild cases characteristic features on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging strongly support the diagnosis and heart biopsy is not usually required. In more severe cases or if patients fail to respond to standard medical care, a heart biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis and guide therapy. There are no specific blood tests to confirm the diagnosis of myocarditis; however, an otherwise unexplained elevation in troponin and/or electrocardiographic features of cardiac injury are supportive. Similarly new heart wall motion abnormalities or a fluid around the heart seen on echocardiography are not specific but support the diagnosis once other more common disorders have been excluded. For example chest pain and shortness of breath with activity can result from many forms of heart disease and non-cardiac causes.

Because the diagnostic tests for cardiac inflammation, magnetic resonance imaging or heart biopsy, are not widely available, the diagnosis is often overlooked. In people who have autoimmune disorders, myocarditis may result from an autoimmune reaction against heart tissues and not a viral infection. In this setting, myocarditis is a part of a more widespread process that may require treatment with medication to suppress the immune system. Myocarditis can also exacerbate the cardiac damage from other rare heart diseases such as amyloidosis. Myocarditis that presents with heart failure symptoms and decreased heart pump function should be treated according to the current national society guidelines for "systolic" heart failure.

Drugs that block the immune system are generally not indicated for the management of the most common forms of myocarditis in adults. However, in specific forms of myocarditis such as giant cell myocarditis, cardiac sarcoidosis or eosinophilic myocarditis, medications that modify the immune response should be considered. These specific forms of myocarditis are diagnosed by heart biopsy. Sports participation during acute viral myocarditis may cause sudden death.

Thus high levels of physical activity following the diagnosis of myocarditis should be avoided for at least 3 to 6 months. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen should be avoided due to a risk of increased inflammation. Myocarditis is a rare cause of cardiovascular disease primarily manifest as sudden death, chest pain or heart failure. The symptoms of heart failure from myocarditis include shortness of breath, fatigue and ankle swelling.

The cause is an inflammation of the heart muscle, most often following a viral infection. Between 0.5 and 3.5 percent of heart failure hospitalizations are due to myocarditis. Most cases of myocarditis are identified in young adults with males affected more often than females.

The diagnosis should be considered in any young adult with unexplained cardiac causes of shortness of breath or loss of consciousness. Many authorities recommend the diagnosis be made by heart biopsy, but imaging with magnetic resonance is growing as an accepted diagnostic method. Specific causes of myocarditis vary by world region, which mandates region-specific diagnostic and management strategies. Approximately 10 to 20 per 100,000 people are diagnosed with myocarditis in the U.S. annually, and in children, the incidence is 1 to 2 per 100,000.

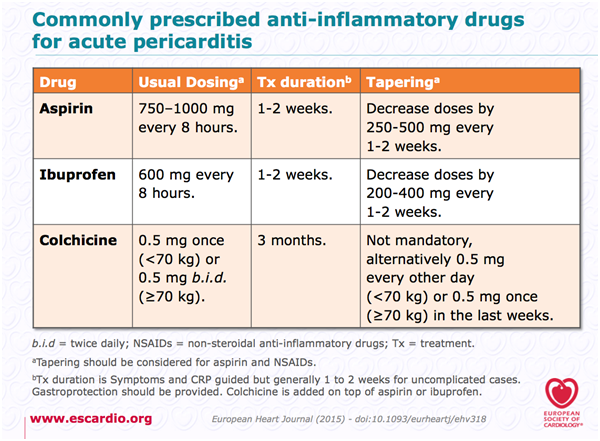

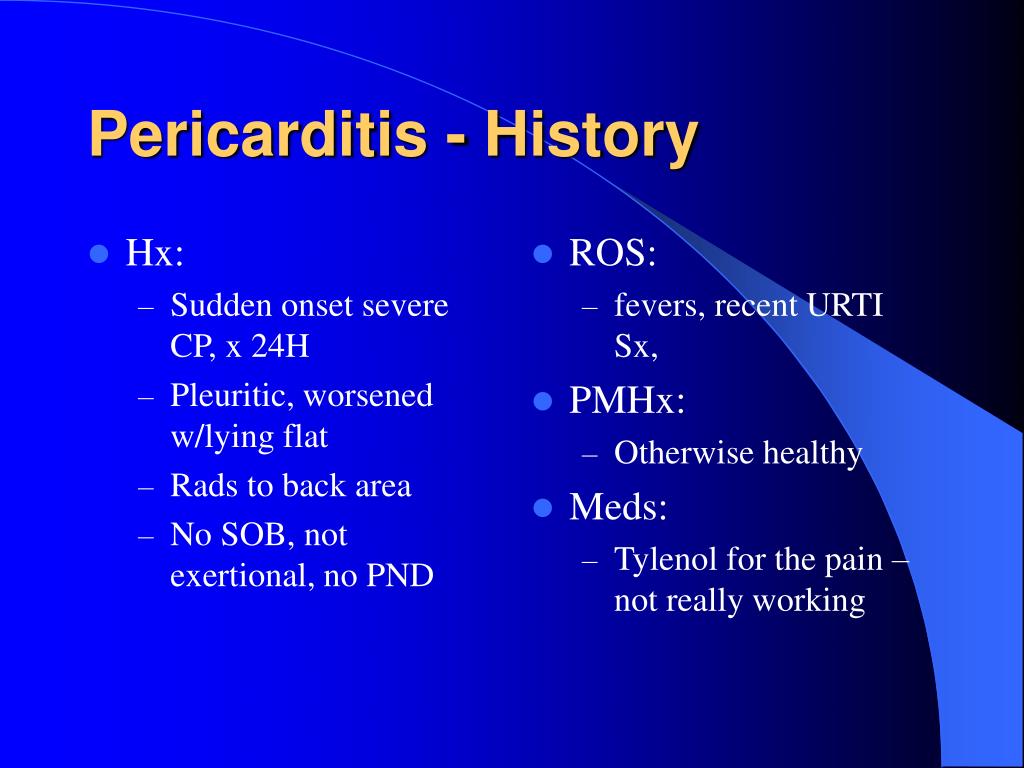

Although many cases resolve on their own or with treatment, leading to a full recovery, severe myocarditis can lead to heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms, shock and sudden death. Signs and symptoms of myocarditis include fatigue, shortness of breath, fever, chest pain and palpitations . Aspirin or NSAIDs are mainstays of therapy for acute pericarditis .

If laboratory data support the clinical diagnosis, symptomatic treatment with NSAIDs should be initiated. Because of its excellent safety, the preferred NSAIDs is ibuprofen in a dose of 600 to 800 mg orally, three times daily with discontinuation if pain is no longer present after two weeks . Many patients have very gratifying responses to the first or second dose of NSAIDs, and most respond fully with no need for additional treatment. Reliable patients with no more than small effusions, who respond well to NSAIDs, need not be admitted to hospital . Patients who do not respond well initially, who have larger effusions, or who have a suspected cause other than idiopathic pericarditis should be hospitalised for additional observation, diagnostic testing and treatment.

Patients who respond slowly or inadequately to NSAIDs may require supplementary narcotic analgesics to allow time for a full response or a course of colchicine . Colchicine is recommended at low, weight-adjusted doses to improve the response to medical therapy and to prevent recurrences . Rest is usually recommended in acute pericarditis and acute myocarditis. Given that myocarditis often leads to hospitalization, this task seems easy to carry out in hospital practice; however, it could be a real challenge at home in daily life. Heart rate-lowering treatments (mainly beta-blockers) are usually recommended in case of acute myocarditis, especially in case of heart failure or arrhythmias, but level of proof remains weak. Calcium channel inhibitors and digoxin are sometimes proposed, albeit in limited situations.

Whether heart rate has an effect on inflammation remains unclear. Several questions remain unsolved, such as the duration of such treatments, especially in light of new heart rate-lowering treatments, such as ivabradine. In this review, we discuss rest and heart-rate lowering medications for the treatment of pericarditis and myocarditis. We also highlight some work in experimental models that indicates the beneficial effects of such treatments for these conditions. Finally, we suggest certain experimental avenues, through the use of animal models and clinical studies, which could lead to improved management of these patients. Presentation of acute myocarditis is variable, ranging from subclinical disease to heart failure and patients can present with chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations and fatigue.

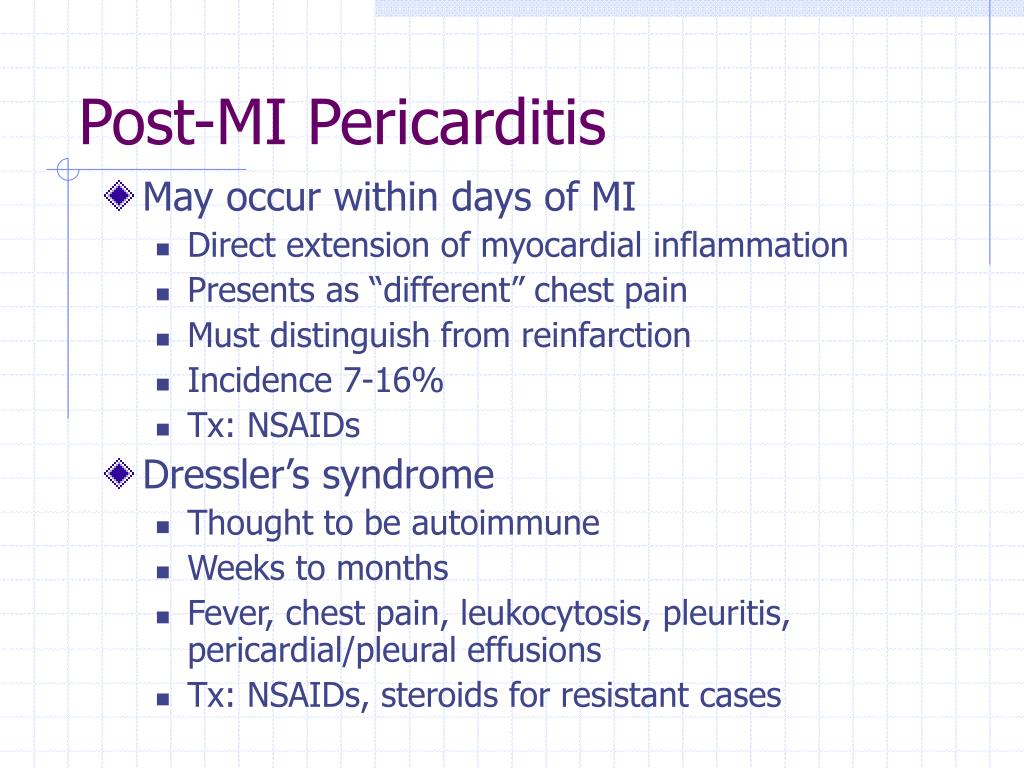

Most patients respond well to standard treatment, and the prognosis is good. However, it can progress to dilated cardiomyopathy and chronic heart failure, with evidence implicating it in 12% of sudden deaths in adults aged under 40. Usually, the cause of chronic constrictive pericarditis is also unknown. The most common known causes are viral infections, radiation therapy for breast cancer or lymphoma in the chest, and heart surgery. Chronic constrictive pericarditis may also result from any condition that causes acute pericarditis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus , a previous injury, or a bacterial infection.

The patient who seeks for medical care complaining of chest pain and shortness of breath is often evaluated for serious heart and/or lung problems. Oxygen is often supplied, a monitor is used to assess heart rate and rhythm and an electrocardiogram is performed to look for potential acute heart attack. Vital signs, including blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature and oxygen saturation may be performed. Heart muscle inflammation is an inflammatory process of the heart muscle, which can be acute or chronic in nature.

When both the heart muscle and pericardium are inflamed it is called either Myo-pericarditis or Peri-myocarditis. In addition to muscle cells, tissue and blood vessels of the heart can also be affected. Heart muscle inflammation is often preceded by a viral infection and is therefore often inconspicuous. The overall health of the person affected and the degree of inflammation are both crucial factors for recovery.

Additionally, it is also very difficult to say when exactly the inflammation has resolved. Myocarditis can affect people of all ages, including those with healthy hearts. The diagnosis of myocarditis usually is made when the doctor puts together clues from several sources, including the patient's symptoms and physical exam, theelectrocardiogram, and several blood tests . If symptoms of heart failure are present, anechocardiogramcan be helpful in assessing the extent of heart muscle damage. Occasionally, a heart muscle biopsy is required to document the extent and type of inflammation present in the heart muscle.

Acute pericarditis presents in a variety of ways, depending upon the underlying etiology. Such patients should be closely monitored for signs of cardiac tamponade, a potentially lethal complication of pericarditis. The symptoms of myocarditis are not specific to the disease and are similar to symptoms of more common heart disorders.

A sensation of tightness or squeezing in the chest that is present with rest and with exertion is common. Not infrequently chest pain is improved with leaning forward and worse with lying back when the inflammation affects the outer lining of the heart or pericardium as well as the heart muscle. If the heart pacing or conduction tissues become inflamed, a slow heart rate may cause fatigue or lightheadedness.

Inflammation can also cause extra beats that feel like a flutter in the chest. Sustained runs of extra beats in quick succession may lead to lightheadedness or even loss of consciousness. Sudden death resulting from a myocarditis-related arrhythmia is an important cause of death in children and young athletes. Direct tissue examination from a biopsy is the standard for proving the presence of myocarditis, which can also identify if viruses are present. Additional screening tests for myocarditis may include blood tests to measure for elevated cardiac enzymes that would indicate heart inflammation or injury, including myoglobin, troponin and creatine kinase. Imaging tests include an echocardiogram or a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to determine if there is any visible injury to the heart or abnormalities in how the heart is functioning.

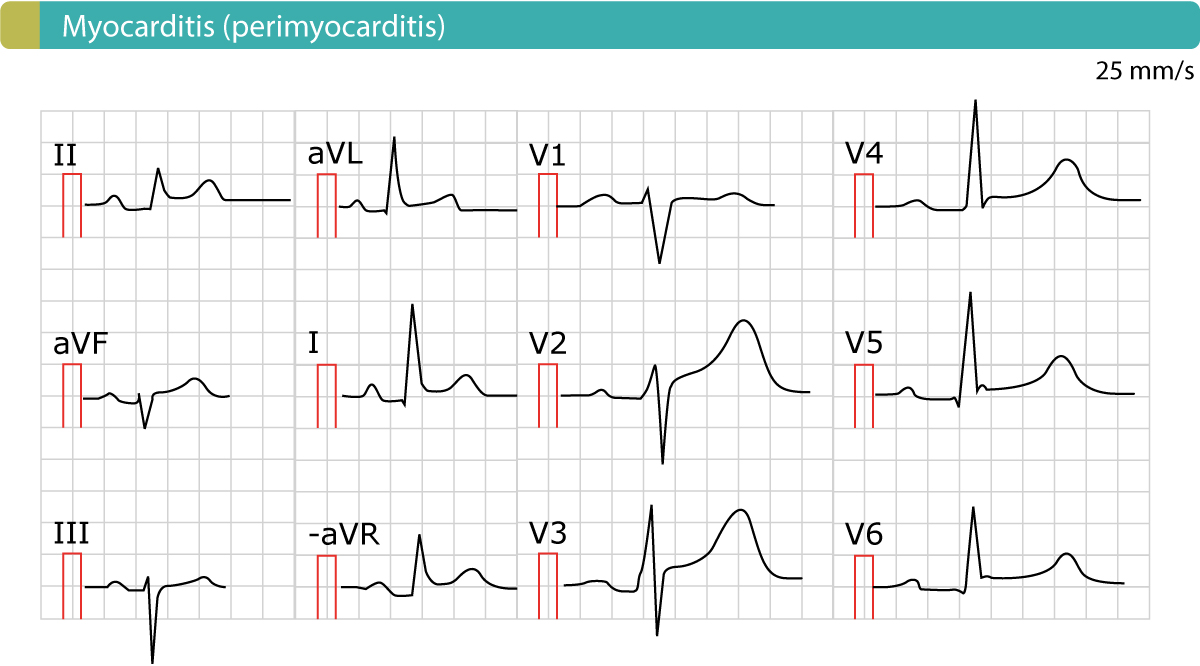

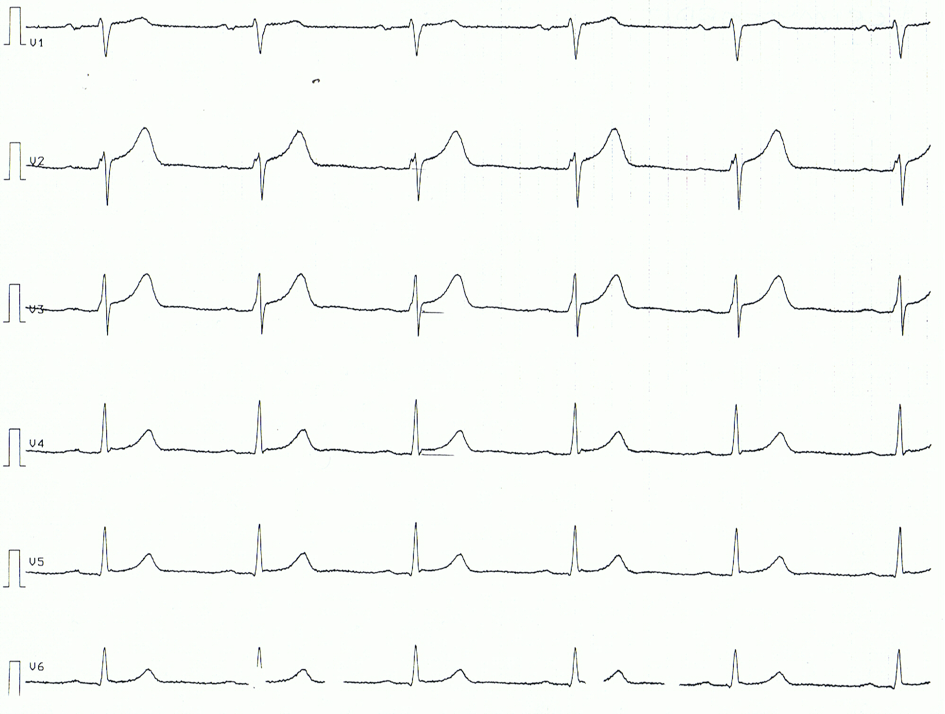

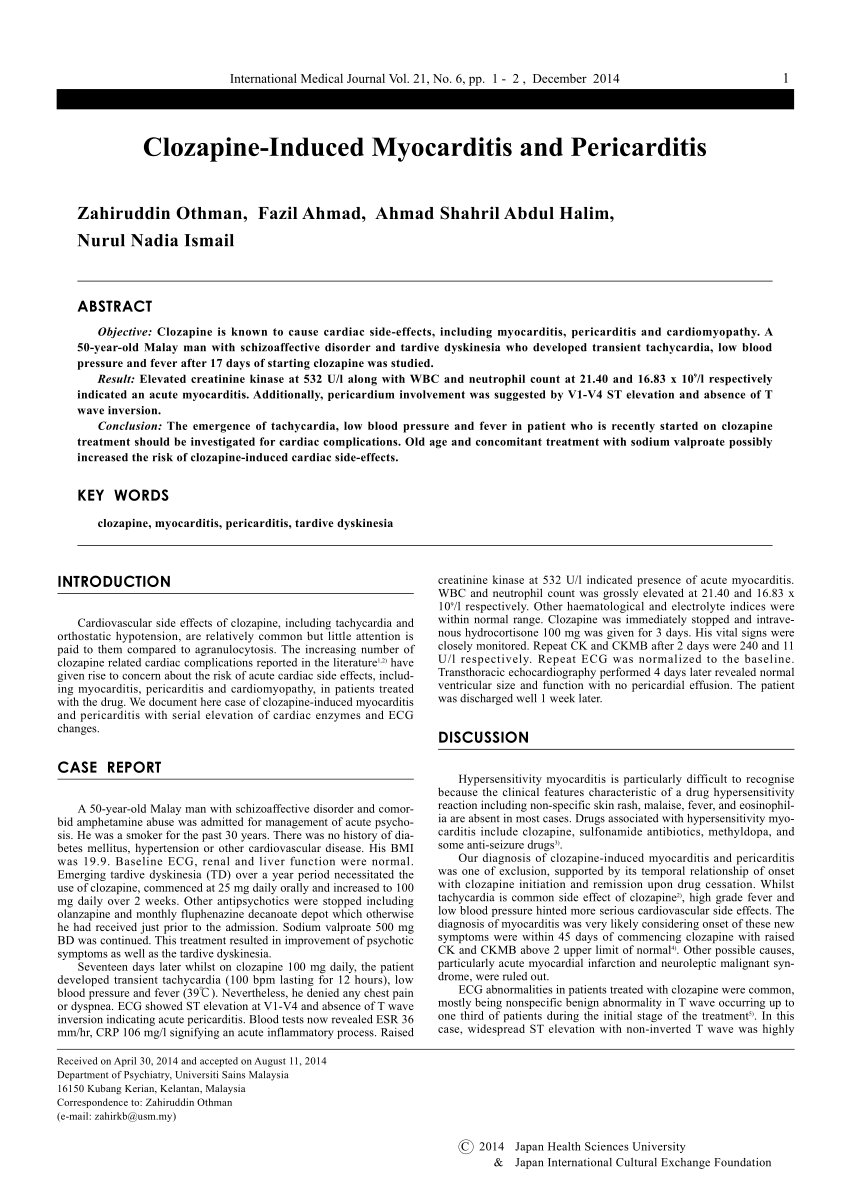

Electrocardiography screening can assess the heart rhythm and may show signs of injury to the heart as well as signs of pericarditis. Pericarditis is often related to myocarditis and involves swelling and inflammation of the pericardium, a thin, sac-like tissue structure that surrounds the heart to hold it in place and help it function properly. Management is based on discontinuation of the causative agent and symptomatic treatment . The use of heparin and anticoagulant therapies is a possible risk factor for the development of a worsening or haemorrhagic pericardial effusion that may result in cardiac tamponade. In a study of 274 patients with acute pericarditis or myopericarditis, the use of heparin or other anticoagulants was not associated with an increased risk of cardiac tamponade . On the other hand, in the setting of co-existing pericardial effusion, full anticoagulation may be a risk factor for tamponade and complications .

If your symptoms last fewer than three weeks, you will be diagnosed with acute pericarditis. If you experience another episode of pain after a four- to six-week period of no symptoms, then the pericarditis is considered recurring. 20 to 30 percent of patients with acute pericarditis will have recurring symptoms. If the pain persists continually for longer than three months, the condition is considered chronic, which may cause fluid around your heart.

Your doctor will work with you to determine the most accurate diagnosis and devise a treatment plan tailored to your specific condition and needs. Whenever you feel chest pains, make sure to visit a doctor immediately or dial for emergency assistance. While many cases of pericarditis can go away without medical treatment, it can sometimes develop into a more serious condition called cardiac tamponade. This occurs when fluid collects in the pericardium, preventing the heart from filling properly and causing a drop in blood pressure that can be fatal.

Receiving an early diagnosis can help prevent these complications and help ensure that you aren't experiencing a more serious heart condition. Pericarditis is an inflammation of the tough fibrous sac around the heart, the pericardium. Like myocarditis, pericarditis is most common in association with a viral infection, but can have other causes, including an immune reaction. The major symptom of pericarditis is chest pain, which is improved by sitting up and leaning forward. The electrocardiogram can serve to identify the inflammation but occasionally it does not show the classic results. Colchicine and anti-inflammatory drugs are the mainstays of treatment, but even without treatment, symptoms usually go away by themselves.

Most of the damage to the heart is caused by the body's immune reaction to the germ, and not by the germ itself. The abnormal immune response may be confined to a small area or involve a large portion of muscle tissue. Often, the more heart muscle that is damaged, the more severe the symptoms. Many drugs used for chemotherapy and certain antibiotics in rare cases can cause an immune response similar to what is seen with viral infections. The heart injury may result directly from a toxic effect such as a toxin or a virus. More commonly myocarditis is a result of the body's immune reaction to the initial heart damage.

Most immune reactions are helpful and serve to clear infections, but sometimes the scar tissue resulting from the inflammation can lead to long term decline in heart function or chronic abnormalities in heart rhythm. Sometimes the immune reaction fails to clear an infection which can lead to chronic viral myocarditis. Myocarditis can also accompany systemic inflammatory disorders such as lupus or Kawasaki disease. The most common symptoms of myocarditis in children include fatigue, shortness of breath, abdominal pain and fever. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of myocarditis and pericarditis with mRNA vaccines and those most likely to be affected. They should be alert to presentations such as acute chest pain, shortness of breath and palpitations that may be suggestive of myocarditis after vaccination, especially in adolescent or young males.

Coronary events are less likely to be the source of such symptoms among younger people. Some patients with severe myocarditis develop low blood pressure despite optimal medical care. These patients may require a temporary heart pump to survive the acute injury.

Some of these patients with myocarditis can be bridged to recovery and have the pump removed. The survival after heart transplantation for adult patients with myocarditis is similar to that for other causes of cardiac failure. Patients with severe myocarditis should be seen by cardiologists with expertise in heart failure and heart rhythm disorder management. Approximately 5-11% of patients with acute pericarditis may have a systematic autoimmune disease . Acute pericarditis could be the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus.

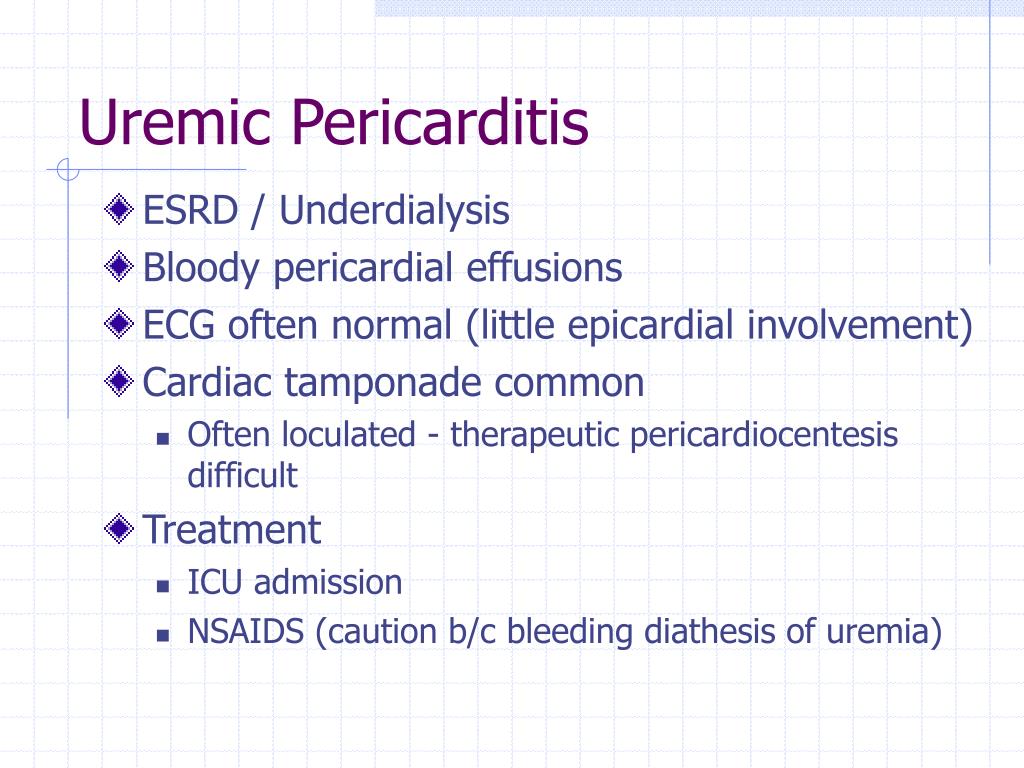

Pericardial involvement is common in Sjögren's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis and sclerodermia, but may also be present in systemic vasculitis, Behçet's syndrome, sarcoidosis and inflammatory bowel diseases. The treatment is especially targeted to the control of systemic disease . The insignificant response to colchicine and the need for adjunctive immunosuppressive agents are clues to the possible presence of autoinflammatory disease . In some of these conditions, anti-IL or anti-TNF agents may be considered. Most patients with acute pericarditis have a good long-term prognosis . Cardiac tamponade rarely occurs in patients with acute idiopathic pericarditis, and is more common in patients with a specific underlying aetiology, such as malignancy, TB or purulent pericarditis.

Approximately 15-30% of patients with idiopathic acute pericarditis who are not treated with colchicine will develop either recurrent or incessant disease, while colchicine may halve the recurrence rate. The proposed triage of acute pericarditis according to epidemiological background and predictors of poor prognosis is presented in Figure 1 . Acute pericarditis can have a similar presentation to myocarditis, with chest pain and shortness of breath, and patients can also have concurrent myocardial involvement, known as myopericarditis. Treatment of pericarditis is aimed at the cause, with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs the mainstay of therapy for viral, idiopathic and pericarditis associated with a systemic inflammatory disease. The long-term prognosis of pericarditis is good, but it can become recurrent and rarely patients can develop constrictive pericarditis. The symptoms of heart muscle inflammation are most often unspecific or may even be absent.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.